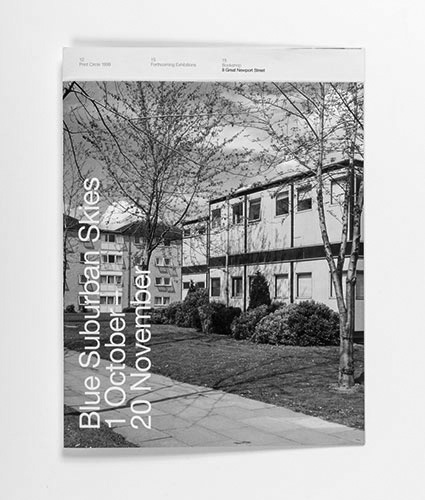

Blue Suburban Skies

Photographs 1998-2000

We all have our visions of suburbia. For many, this vision is utopian; for many others, it is a vision of hell. How can a place provoke such strong feelings? Like utopia, like hell, does suburbia exist at all, or is it simply an idea, rather than an ideal?

The city has been one of the most important influences upon the thinking, and the art, of the twentieth century, and for most, the city has been exclusively urban. This is a mistake, a short-sightedness which this exhibition and its events will explore. Blue Suburban Skies will allow important American work from the 1960s and 1970s to create an historical context for contemporary work by artists based in Britain, such as Nathan Coley or Nigel Shafran. Rather than the bland homogeneity with which we might associate suburbia, the work in this exhibition will show it as a much more complex place, a place of repressed conflict, of quiet disturbance.

Suburbia is a place of contradictions. It is an essential part of the city and an escape from it. It is familiar although it may not be instantly recognisable. It is ubiquitous and, perhaps as a result, almost invisible. It is safe yet prone to vicious outbursts; predictable, yet never entirely free of the unknown. It is the place of the family, and so also a home for disaffected youth, the neatly tended lawns and ponds the spawning grounds for punk and teenage rebellion. The lawnmower and The Jam, squeaky chamois and the Sex Pistols; these are the sounds of the suburbs.

Jeremy Millar, artist and curator living in Whitstable, England, 1999

close

"Many people like suburbia," wrote the architect Robert Venturi, with a faintly wondering air, in Learning from Las Vegas. He was almost right. What many people actually like is the idea of suburbia, this being a place that by definition includes the following: prosperity, order, space, privacy, hedges, self-determination. Suburbia, that is to say, is a misnomer. It is an imagined place, not the outcome of some extended urban impulse but of a contra-urban one. Suburbs are actually anti-urbs. They are built not from a desire to replicate the city, but to invert it.

And here's the joke: build outwards from urban disorder to the leafy oases beyond and you destroy them. Just to compound the irony, the progression is algebraic. Leave a suburb long enough and it will become an urb, requiring its own suburb until, as H. G. Wells predicted, there is nowhere left to escape to and reality has to be faced. The Rowntree report on suburban Britain didn't catalogue a new malaise, merely the terminal stages of an old one.

If you're feeling particularly millenarian, you might like to see this process - dream, reach for dream, destroy dream - as being at the heart of the human comedy. Read Agamemnon or Macbeth and the impulse seems potentially tragic; but because suburbia is about little people, it is comic instead. Whose heart was not secretly cheered by Cynthia Payne beating Knightsbridge toffs in Streatham, or by Melita Norwood bottling chutney in Tooting and selling state secrets filched from SW1? (Who - what Waugh or Amis - could have improved on their surnames?) Anthony Blunt, who lived and spied in the West End, was the sinister stuff of high art. Melita Norwood lives in some variant of Acacia Avenue and is a figure from a sitcom.

It is not just the smallness of suburban life that makes it comic. Like the whole idea of rus in urbe, it is the endlessly self-defeating nature of the suburban dream that provokes laughter. Suburbia is like some character in an Escher print, constantly bumping into itself walking in the other direction. Something of the risible pathos of this can be seen in "Blue Suburban Skies", a show at London's Photographers' Gallery. Nathan Coley's Villa Savoye (1997) - an install- ation that juxtaposes slides of an average developer's semi with a soundtrack declaiming Le Corbusier's views on the ideal suburban villa - is all about the void between aspiration and reality. "The hearth is built simply of brick, expressing function," intones a voice in the pinched suburban tones of Morningside, while Coley's slide projector, marginally off-cue, cuts to a fake Georgian chimney piece buried in knick-knacks and gewgaws. "At piano nobile level, a continuous strip of glazing acts as a frame for the landscape" introduces a panorama of Crittall's leaded lights shrouded in ruched chintz.

Coley's seems a positively kindly view when compared with Michael Danner's portrait of suburbia as Toytown. The impact of Danner's work lies in its finish, his photographs being identically flat, rectangular, airbrushed, matt, clear-lit, neatly framed and shadowless. His pictures are ludicrously idealised images of a world based on ludicrous ideals: identical, ersatz village houses built in an arcadian glade which Danner's cruel camera shows to be a redundant gravel pit. What makes this such a painful work is that it so nearly seems to live up to the suburban dream of the exhib- ition's title. The images would be so pretty, the life they portray so neat, were it not for the almost invisible irruption of pylons, burglar alarms and barbed wire peeping through the pollarded willows.

Could Danner have produced such an agonisingly sharp view of suburbia had he not been, at some level, in love with it? It is a question you find yourself asking again and again as you walk through "Blue Suburban Skies": appositely enough, since that same ambiguity probably sums up your own feelings on the subject. It certainly seems to be behind Nigel Shafran's series, Dad's Office, whose painterly images of what looks like North Finchley love their subject almost as obviously as they hate it. The Ovaltiney palette of Shafran's work, the workaday patterns into which his photographs fall - a Cristal d'Arques bowl on an opened telephone directory, the effulgence of a bloom of damp - all speak of familiarity, maybe even of nostalgia. What these empty rooms also hint at, though, is a life unfulfilled, letters left unopened, dreams unrealised. The inbuilt disappointments of suburbia and those of family life become indistinguishable from each other in Shafran's lens: in fact, familiarity and the suburbs become the same thing.

Maybe that's where the endless appeal and eternal ridiculousness of Pinner both lie. Suburbia is a dream of childhood, comforting and suffocating by turns. Eyal Weizman's Eruv catalogues the fight over the move by a group of Orthodox Jews to erect a single wire strand, defining an area of sabbath observance, around a part of Hampstead Garden Suburb. Weizman's work shows the impulse to enclose as only marginally weirder than the impulse to fight it: "Sure, it's absurd and irrational to believe your life is going to be changed by the presence of a wire," reads one of the documents in his installation, "but it's even more absurd and irrational to oppose it." What emerges is some kind of Freudian story of civilisation and its discontents, of people forced to live in society but who secretly want the world for themselves. It's a nasty idea, and a seductive one. Stand in the eruv that Weizman has made with his photographs around the gallery walls and you can't wait to get out; except that the images are so appealing, somehow.

Darwent, Charles: ‘Neat Dreams’, New Statesman, London 8 November 1999,

pp. 41-21

close

2001

Without the Big Events of History Clifford Chance, London

1999

The Photographers' Gallery, London, commissioned and curated by Jeremy Millar

2001 Without the Big Events of History Clifford Chance, London

1999 The Photographers' Gallery, London

1999 The Photographers' Gallery, London, booklet

close